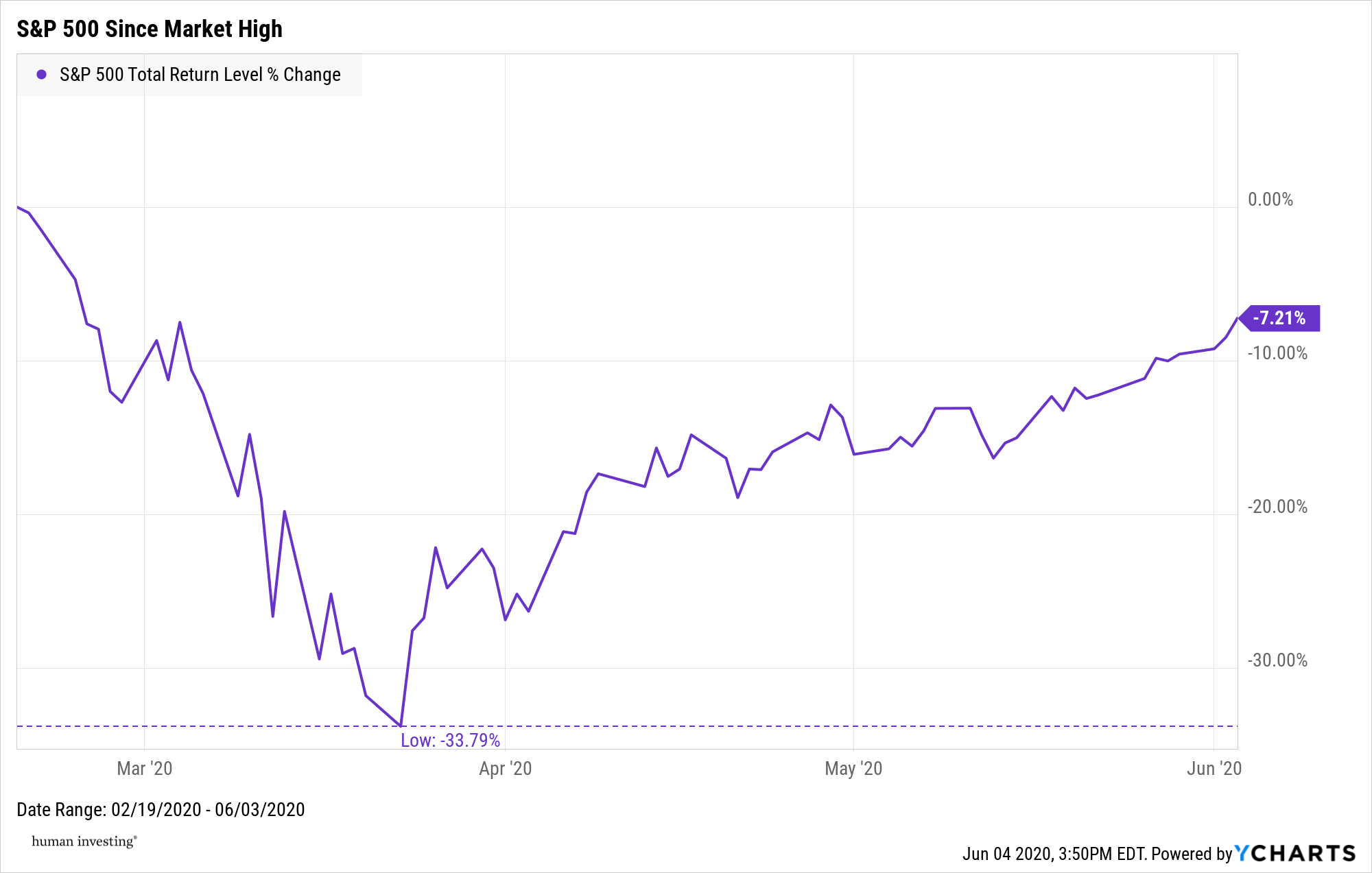

A global pandemic and dislocated markets can teach us a lot if we take the time to listen and observe what our clients are saying. Today was a day full of trying to explain the concept of diversification. Where, in a single account, we can own both stocks and bonds— with each having a distinct purpose. Given the prolific stock market sell-off, if a client has any amount of equity investments in their account, they are down, almost universally. If a client has one million invested and one-half of those funds are in stocks that are down thirty percent, their overall portfolio is down $150,000 or 15%, even with the other fifty percent of their account in CDs or Cash. For some, this is overwhelming, and more than they can handle. But should it be?

“All my investments are at risk.”

Today, I learned from this situation, that a client thought the 15% loss meant that all of their investments in their account were risky. In reality, one half of their account is in FDIC insured CDs and U.S. Treasuries—collectively, some of the safest investments in the world. While at the same time, just half of their account was causing the loss, and the "risky" portion of their account was half in blue-chip, dividend-paying companies. So, what was I missing or, the client not getting? Why were they freaked out by the volatility when they had TEN YEARS worth of cash and bonds on hand? Enter the theory of mental accounting and the concept of categorization or labeling.

The Decisions That Comes From Mental Accounting

Mental accounting posits that people treat money differently—particularly when looking at its intended use. For this client (and probably many of us,) it would have been better to put their bonds and safe investments into one account and their riskier and more volatile investments in another. Even though they would have no more or less invested in bonds or stocks, the mere fact that they are separated allows for them to categorize or label those accounts "safe" and "risky" and know there is a moat between the two of them.

Fortunately for this client and me, I was able to explain that although not in separate accounts, the investments were, in fact, different, with one portion of the account safe, and the other part of the account earmarked for drawing on many years from now. Regardless, I learned a valuable lesson about the cognitive dislocation, and bias, of mental accounting. And, how regardless of whether I have accounted for the proper mix of stocks and bonds in a client account, if they don't get it, they may force my hand and require that I sell because they view it all as risky. Noted.

Understanding the Role of Your Retirement Accounts

Similarly, I was speaking to another client that was concerned about their 401(k) account and the recent volatility. They asked if we should change things up given; we had "lost money." They were suggesting these funds should feel more like their cash and bond accounts. After checking to make sure I wasn't losing my mind and seeing that they were invested 75% in equities and didn't need to access the money for twenty plus years, I wondered what I was missing. What I was missing was another bias that is part of the theory of mental accounting.

Wealth accounts and "money hierarchy" was first explored by behavioral pioneers Dr. Hersh Shefrin and Dr. Richard Thaler (1988). In their analysis, they suggest there is a money hierarchy whereby funds can be placed in locations in order of how tempting it can be to gain access. Practically, a checking and savings account are easily accessible in "in-reach," therefore, they should be invested conservatively. While at the same time, a 401(k) or IRA is for later in life and relatively inaccessible and "out of reach" and, as a result, should be invested more aggressively than checking and savings.

For this client, I was able to explain that although their equity allocation was more significant than other accounts, the reason was that this was a long-term account. Further, I shared that these funds should be out of reach, given the taxes and stiff penalties for early withdrawal. Thaler's research (1999) suggests that an individual's propensity to spend money from cash and savings accounts was high, while their desire to spend from retirement accounts was near zero. Although 401(k) loans are more common today than they were twenty years ago, retirement accounts are still the least liquid and "out of reach" funds for most clients. Therefore, most commonly, retirement accounts should be invested more aggressively than other, more short-term accounts. The resulting investment volatility can be far higher than an individual might experience in their cash or savings accounts, but that does not mean the funds are invested poorly. Instead, it helps to underscore Shefrin and Thaler's work from 1988 and assigns a hierarchy to client capital and subsequent investment experience/expectations.

Being there for the behavioral aspects of investing

We (advisors and clients) grossly underestimate the behavioral aspects of investing. Bias exists on everyone's part. Understanding bias (such as mental accounting) can help both clients and advisors make healthy choices with lasting benefits. I learned a lot today—and was able to work with several clients to make sure that what was learned, resulted in good decisions and positive outcomes for today and well into the future.

Reference

Thaler, R. H. (1999). Mental accounting matters. Journal of Behavioral decision making, 12(3), 183-206.

Shefrin, H. M., & Thaler, R. H. (1988). The behavioral life‐cycle hypothesis. Economic Inquiry, 26(4), 609-643.