Volatile markets test more than portfolios—they test patience. It’s easy to feel unsettled when headlines scream, and market volatility ensues. But the most important thing you can do as an investor is also the simplest: don’t let emotions get the best of you.

In my nearly 30 years of advising clients, I’ve seen over and over again: the clients who succeed are the ones who manage their emotions, not just their money. The smartest thing you can do right now is stay calm and stay the course. The plan is working—even when it doesn’t feel like it. My experience has been that history has a way of rewarding those who stay calm, stay invested, and stay focused on their well-crafted financial plan.

At Human Investing, we believe that behavior, not timing or speculation, is what separates long-term success from short-term regret. For clients who have been with us for over 20 years, you’ve seen firsthand how a steady, disciplined approach can weather storms and grow wealth through them. For those new to our firm, please know that trust is the foundation of everything we do. We don’t just manage portfolios, we help guide people through uncertainty with clarity, care, and confidence.

To better understand the importance of maintaining a disciplined investment approach, it is helpful to examine five common psychological biases that often lead investors to deviate from sound decision-making. Drawing on both empirical research and professional experience, this section explores how emotional responses can override strategic thinking—particularly during periods of heightened uncertainty and market volatility—and outlines methods used to help clients remain focused on long-term objectives.

1. Loss aversion: When pain is louder than logic

Researchers Kahneman, Knetsch, and Thaler (1991) discuss the psychological factors that drive loss aversion. Loss aversion is not just an investing concept; it’s a fundamental part of human psychology. Research shows that losses are felt about twice as painful as equivalent gains are perceived as pleasurable. In the brain, a $100 loss doesn’t just “sting”—it screams. And when markets drop, that emotional volume can drown out logic, strategy, and even years of sound advice.

This isn’t just a theory. I've seen it firsthand for a few decades—watching clients grapple with fear during the dotcom bust, the 2008 financial crisis, the 2020 COVID crash, and more recent volatility. In each case, the market eventually recovered. But those who let fear dictate their choices often miss the recovery, lock in their losses, and derail their long-term plans.

Here’s what makes loss aversion so dangerous: it feels rational. When the market drops 20%, the brain doesn’t think, “This is temporary.” It thinks, “Get out before it gets worse.” That impulse can feel like wisdom. But in reality, it's a trap.

The dislocation occurs when investors stop viewing a dip as part of the journey and begin to see it as the destination. Their long-term goals fade from view. The carefully designed plan becomes irrelevant. All that matters is stopping the pain.

But that short-term relief often comes at a prohibitive cost. Investors who sell at the bottom lock in their losses and are frequently too emotionally exhausted—or too afraid—to re-enter the market in time for the rebound. And rebound it almost always does. History shows that the market has consistently rewarded those who stay invested through downturns, not those who try to time their exits and re-entries.

2. Herding: When “everyone’s doing it” feels safer than thinking

There’s a reason why stampedes are dangerous—not everyone in the crowd is running toward opportunity. Some are running from fear.

In investing, we refer to this behavior as herding—the instinct to follow the crowd, particularly during times of uncertainty. Scharfstein and Stein (1990) were among the earliest to formally investigate and publish on the concept of herd mentality. We are indeed social creatures, hardwired to look to others for cues when we’re unsure. But in the markets, that instinct can be costly.

When prices drop and headlines grow loud, it’s natural to wonder: “What does everyone else know that I don’t?” You see friends moving to cash, analysts shouting about doom, and articles predicting disaster. The pull to join the herd becomes magnetic. But the crowd is often most unified at the wrong time, buying high out of excitement or selling low out of fear.

Here’s the cognitive dislocation: when fear spreads, we confuse consensus with correctness. If enough people are panicking, their emotion starts to feel like evidence. But markets are not democratic. The loudest voices are not always the wisest, and just because many are moving in the same direction doesn’t mean it’s the right one.

3. Recency bias: When yesterday becomes forever

Tversky and Kahneman (1974) laid the foundational research on recency bias. They determine that “…the impact of seeing a house burning on the subjective probability of such accidents is probably greater than reading about a fire in the local paper. Furthermore, recent occurrences are likely to be relatively more available than earlier occurrences (p. 1127).”

Put differently, individuals often extrapolate recent market movements into the future, believing that a market decline will persist or that a rally will continue indefinitely. This cognitive distortion, known as recency bias, reflects the tendency to overweight recent experiences when forming expectations about future outcomes.

It’s a mental shortcut that makes sense on the surface. After all, if it’s been raining for three days, we naturally reach for an umbrella on day four. But in the markets, this shortcut becomes a trap.

The dislocation happens when investors confuse a recent event with a long-term trend. They think: “The market’s been down the last two months—maybe this time is different. Maybe it won’t recover.” Or: “Tech has been hot all year—maybe it always will be.” This kind of thinking leads to chasing what has already happened or fleeing from what is already priced in.

Here’s the problem: the market doesn’t move in straight lines. It zigs, zags, and surprises. The best days often follow the worst. Yet, when recency bias takes hold, investors tend to anchor on the latest data point and overlook the broader context.

I’ve witnessed this bias unfold in every major market event since 1996. This ‘cognitive dislocation’ was particularly acute during the downturn from 2000 to 2002, when markets declined by 10%, 10%, and then 20%. But those who were paralyzed by recency bias—those who assumed the storm would never end—missed the sunshine that followed.

4. Sentiment: When moods masquerade as markets

The market is often described as a voting machine in the short term and a weighing machine in the long term (Graham, 2006). That’s another way of saying: in the short term, emotion can drive price more than value. And that emotion, called market sentiment, can be just as contagious and unpredictable as the weather.

Sentiment isn’t about fundamentals. It’s about how investors feel about the future. When people feel optimistic, they see opportunity in every dip. When they feel anxious, even the strongest companies look shaky. This is where the dislocation happens: investors begin to substitute their mood for actual analysis.

In times of high sentiment, people often buy more than they should, take on more risk than they realize, or ignore warning signs. During low sentiment, they often underinvest, sell too soon, or abandon long-term strategies altogether—not because the plan changed, but because their feelings did.

I’ve witnessed this in action many times since 1996, particularly in 2008, when panic dominated sentiment, and many investors fled the market near the bottom. The truth is, markets don’t care how we feel. But our feelings often shape how we interpret the market. That’s why at Human Investing, we spend as much time helping clients manage their emotions as we do managing their investments. We help you separate how you feel from what’s actually happening.

Your plan is designed to withstand emotional swings. It assumes there will be times when the market is overconfident, and times when it’s too afraid. That’s why we don’t react to moods. We respond to goals. Because when you confuse sentiment for truth, your portfolio becomes a mirror of your emotions. But when you trust your plan, your portfolio becomes a reflection of your purpose.

5. Emotional echo chambers: When biases team up to derail you

If loss aversion, herding, recency bias, and sentiment were minor on their own, we might be able to brush them off. But they don’t stay in their lanes. These biases often compound, amplifying each other until an investor is no longer thinking clearly. That’s what we call an emotional echo chamber—a space where your own fears are repeated and reinforced until they sound like facts.

Here’s how it plays out:

The market dips, triggering loss aversion—“I can’t afford to lose more.”

You see others selling, which activates herding—“Everyone’s getting out. Maybe I should, too.”

You assume the recent downturn is the new normal—recency bias—“It’s just going to get worse.”

Your confidence drops, and negative sentiment clouds your judgment—“I don’t feel safe, so maybe I’m not.”

Suddenly, your investment decisions are no longer tied to your long-term goals—a chorus of emotional responses drives them, each one echoing the others. This is the moment investors often make their biggest mistakes: abandoning well-designed plans, selling at market lows, or shifting strategies midstream out of fear.

I’ve seen this cycle emerge during every major downturn. What I’ve learned is this: when fear gets loud, clarity gets quiet. Investors don’t just lose money in these moments—they lose confidence, perspective, and peace of mind.

At Human Investing, our job is to help you break out of that echo chamber. We’re here to re-center you when everything feels off-balance, to remind you of the purpose of your financial plan, and to bring you back to your long-term vision when the short-term noise becomes deafening.

We believe that staying invested is not just a financial decision, it’s an emotional discipline. That’s why we design portfolios that align with your comfort zone and why we lead with planning. Because a sound financial plan doesn’t just grow your wealth, it protects your thinking.

When emotional noise is high, we help you find quiet confidence. When biases clash in your head, we help you hear your goals again. And most importantly, when you start to feel like you’re the only one holding steady, we’re here to remind you—you’re not.

Empirical evidence

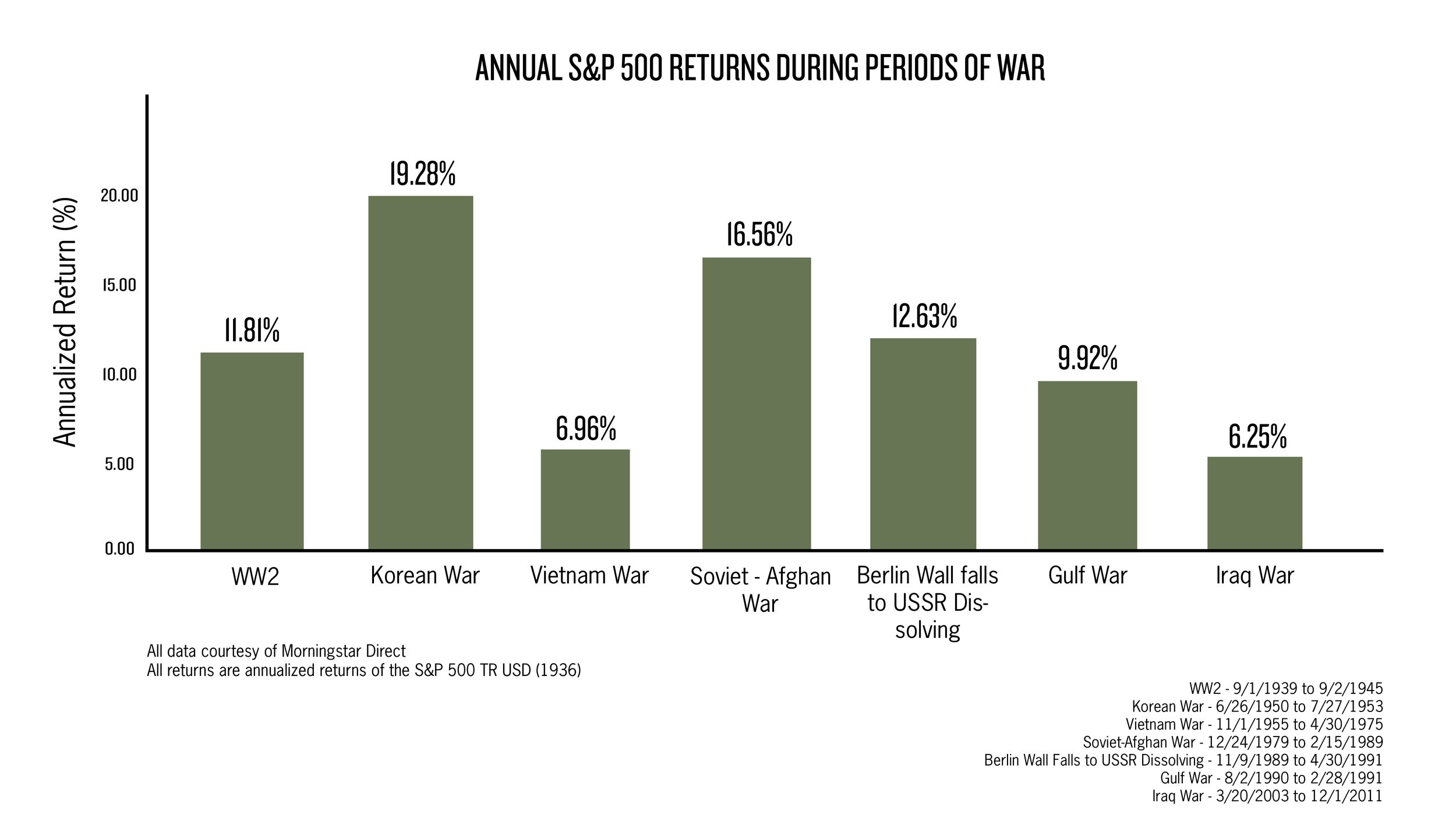

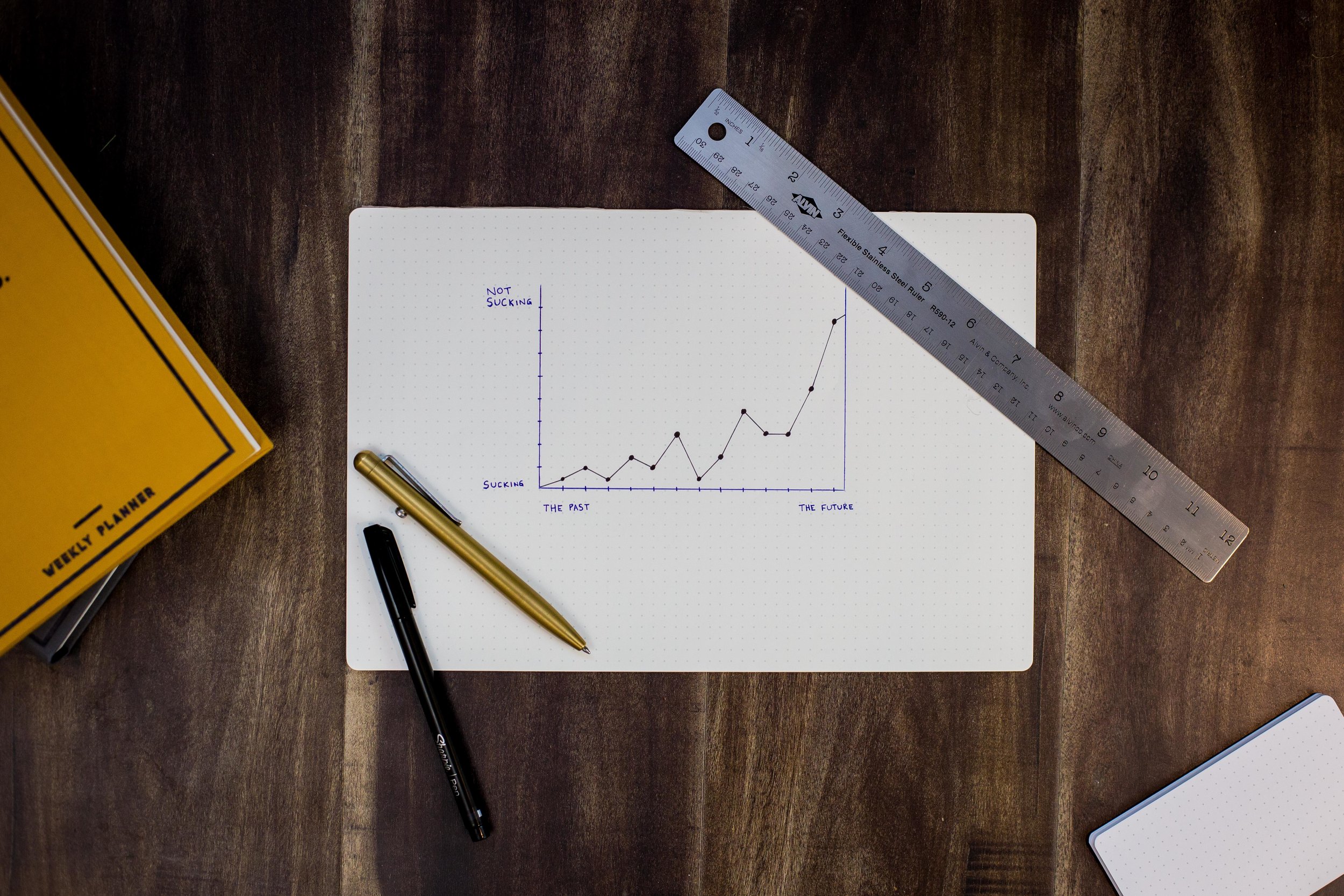

If the five behavioral prompts are not enough to encourage you to focus on your plan, a 40-year perspective on market ups and downs can provide an essential viewpoint.

Please see Figure 1 at the end of this document. In it, you’ll see the average intra-year drop for the S&P 500 is approximately 14%, based on historical data going back several decades.

This means that in a typical year, the market will experience a peak-to-trough decline of around 14%—even in years that end up positive overall.

Here’s a quick breakdown:

From 1980 through 2023, the S&P 500 had:

Positive returns in about 75% of those years

But it still experienced an average intra-year decline of ~14%

Why it matters:

Many investors panic during temporary drops, thinking something abnormal is happening. In reality, a 10–15% drop in a given year is a feature, not a flaw, of long-term investing. It’s part of the process, not a sign to change course.

References:

Graham, B. (2006). The intelligent investor: The definitive book on value investing (Rev. ed., J. Zweig, Commentary). Harper-Business. (Original work published 1949)

Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. L., & Thaler, R. H. (1991). Anomalies: The endowment effect, loss aversion, and status quo bias. Journal of Economic perspectives, 5(1), 193-206.

Scharfstein, D. S., & Stein, J. C. (1990). Herd behavior and investment. The American economic review, 465-479.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases: Biases in judgments reveal some heuristics of thinking under uncertainty. science, 185(4157), 1124-1131.

Disclosures: These market returns are based on past performance of an index for illustrative purposes only. Past performance does not guarantee future results. All investing involves risk, including the loss of principal. Index performance is provided for illustrative purposes only and does not reflect the performance of an actual investment. Investors cannot invest directly in an index.

The information provided in this communication is for informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as investment advice, a recommendation, or an offer to buy or sell any securities. Market conditions can change at any time, and there is no assurance that any investment strategy will be successful.

Diversification does not guarantee a profit or protect against a loss in declining markets. Asset allocation and portfolio strategies do not ensure a profit or guarantee against loss.

The opinions expressed in this communication reflect our best judgment at the time of publication and are subject to change without notice. Any references to specific securities, asset classes, or financial strategies are for illustrative purposes only and should not be considered individualized recommendations.

Human Investing is a SEC Registered Investment Adviser. Registration as an investment adviser does not imply any level of skill or training and does not constitute an endorsement by the Comission. Please consult with your financial advisor to determine the appropriateness of any investment strategy based on your individual circumstances.