The financial world can be a confusing place filled with jargon, technicalities, and little to no guarantees. Research suggests that those who are financially literate tend to have better financial outcomes. Financially literacy is typically measured by asking some core financial concept questions. Let’s walk through some financial literacy questions from the National Financial Capability Study, and explain the why behind the answer. Feel free to guess and score yourself at the end:

Question 1 - interest:

Suppose you had $100 in a savings account and the interest rate was 2% per year. After 5 years, how much do you think you would have in the account if you left the money to grow?

A. Less than $102

B. Exactly $102

C. More than $102

Answer: C, more than $102.

Explanation: The key part here is “After 5 years”. We are told the interest rate is 2% per year. That means every year, 2% gets added to our principal balance. To break it down year by year:

The interest earned increases each year. This is due to compound interest: the original principal ($100) grows, and the interest you earned previously (in year 2, $2) both earn interest. At the end of 5 years, we have $110.41 which is C More than $102.

Why this matters: Interest affects you when you save money to grow it, or borrow money to pay it back later. Knowing how interest can work for or against you is critical for financial success.

Question 2 - inflation:

Imagine the interest rate on your savings account was 1% per year and inflation was 2% per year. After 1 year, how much would you be able to buy with the money in this account?

A. Less than today

B. Exactly the same

C. More than today

Answer: A, Less Than today.

Explanation: They key here is the inflation rate is higher than the savings rate. Inflation is growing at 2%, meaning the price of goods (rent, utilities, food, cars, etc.) is going up by 2% each year. The cost of $100 of goods today will be $102 in 1 year. Your interest on savings is growing at 1% a year. That means in 1 year you will have $101 to spend on goods. In 1 year, you will have $101 to buy $102 worth of goods. Your ability to buy is A less than today.

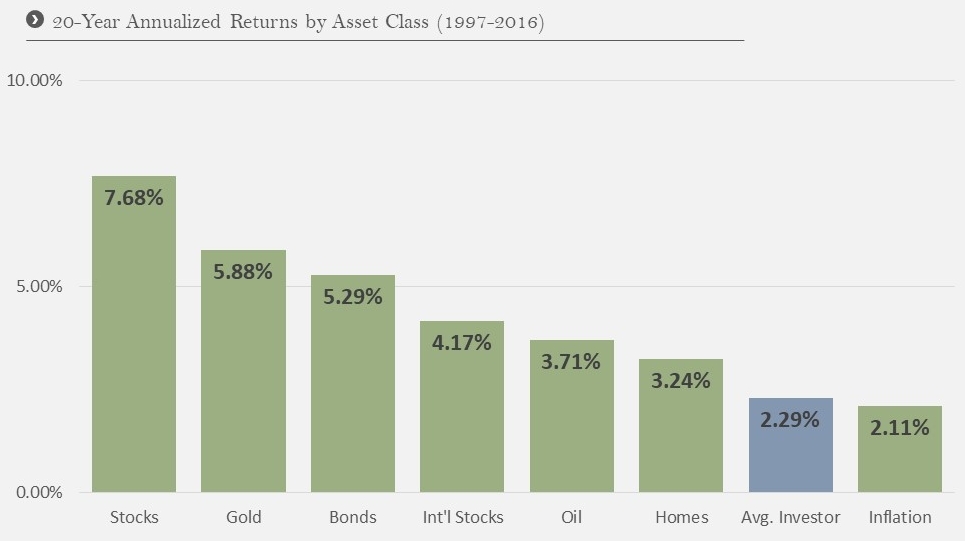

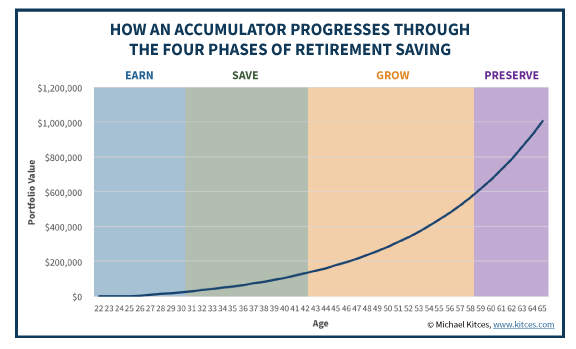

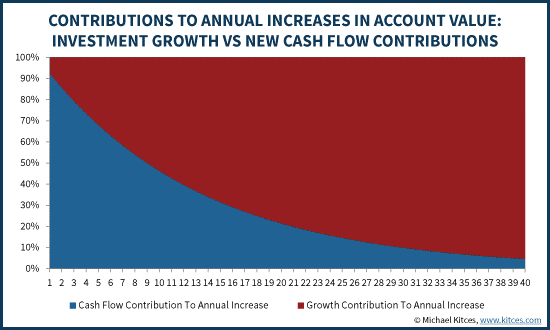

Why this matters: Even if you keep your money “safe” in the bank or under the mattress, inflation is going to make that money less and less valuable. Thus why investing is so important. Investing can be scary due to downturns in the market, but ultimately the odds are in your favor to grow your money over time. Unless you can save significant portions of your income, growing your savings faster than inflation is critical for being able to retire.

Question 3 - Risk Diversification:

Buying a single company’s stock usually provides a safer return than a stock mutual fund.

A. True

B. False

Answer: B, False.

Explanation: To answer this question correctly, it is important to understand both risk and that a mutual fund owns a variety of companies. They keyword here is safer. Financial markets have two types of risk: market risk and company-specific risk (aka systematic risk and nonsystematic risk respectively).

Market risk refers to risk all companies face. Examples of market risk include a change to the US tax code, a global pandemic, or shifts in consumer tastes like a shift from fast food to organic freshly prepared food. You will always face market risk because every company is exposed to these risks. Company-specific risk refers to risks unique to one company. Examples of company-specific risk include sudden changes in management, a press release about product defects, mass recalls, or a superior/cheaper product released by a rival company. Because you own a variety of companies in a stock mutual fund, you diversify away (i.e. reduce your risk) if any single, specific company has a terrible event.

Why this matters: Don’t invest all your money in one company. Especially if you work for that company, and your compensation is based on the company doing well. By spreading out your investments, you reduce your risk of catastrophic returns, and smooth out the ride so you can sleep at night.

Question 4 - interest of the life of a loan:

A 15-year mortgage typically requires higher monthly payments than a 30-year mortgage, but the interest paid over the life of the loan will be less

A. True

B. False

Answer: A, True.

Explanation: Because of the shorter life of the mortgage loan, you pay less interest. Remember in question 1, interest compounds every year. When you borrow money, that compounding works against you. Therefore, the faster you are paying off debt, the less time for interest to compound and grow the total amount you have to payoff. The monthly payments are typically larger, but the overall interest paid is less.

To illustrate with numbers, let’s look at the difference between a 15 year & 30 year mortgage, assuming a 5% interest rate for both:

Why this matters: You can see from the example how much money is saved by opting for a 15 year mortgage. Can you afford that extra monthly payment? That’s worth investigating, but you’ll never explore your choices if you don’t know what they are. You can also usually get a lower interest rate for shorter term debts, which saves you even more money. Anytime you borrow any amount of money, the faster you can pay it off, the less you will pay total. Even if you don’t get a lower rate on the debt, if you pay off the principal sooner, that means there’s less interest compounding against you. When looking to borrow money, evaluate what term (length of time) works best for you and your budget. You want to minimize your cost of borrowing, but you also want to give yourself enough flexibility that you’re confident you will make all those payments on time, regardless of what life brings.

Question 5 - Bond prices and interest:

If interest rates rise, what will typically happen to bond prices?

A. They will fall

B. They will stay the same

C. They will rise

Answer: A, they will fall.

Explanation: This is the question most people get wrong. A bond is government or corporate debt. The government or company pays you coupons (interest payments) based on the issued interest rate. At the end of the bond’s life, it matures, and you get the principal back.

Imagine Disney issues bonds paying 5% interest, the current market rate. You purchase a bond for $1,000, and you get a $50 coupon payment from Mickey Mouse every year until the bond matures. If interest rates rise next year (say to 8%), and Disney issues new bonds, they will issue them at the new interest rate. Your neighbor Laura decides to buy $1,000, and she gets an $80 coupon from Mickey Mouse every year. Because interest rates rose, the value of your bond paying $50/month goes down in value, less than $1,000, because the $1,000 could buy Laura’s bond paying $80/month. The reverse if also true. If rates had fallen to 3%, Laura’s bond would only pay her $30, and your $50/month bond would be worth more than $1,000.

Why this matters: Interest rates change over time. This causes bond prices to change. Bonds will still be less volatile than equities, but they do also fluctuate in value. Don’t panic when you see interest rates rise, and your bond prices going down in value. This is both normal and expected. Rising interest rates are also usually a healthy sign for the economy, and so your equities will generally be rising in value to help offset the loss in value of your bonds. The reverse is also true here. Falling interest rates tend to indicate a less healthy economy (think about when rates have dropped significantly & quickly; the 07-08 financial crisis and COVID-19) which means falling stock prices. Because they don’t tend to move together (uncorrelated), bonds and stocks are an excellent pair for smoothing out your investment returns.

How did you do?

If you got some questions wrong, I hope you understand the why behind the answers and how to utilize this knowledge to better your financial life. If you have questions about financial vocabulary or systems you’d like me to blog about, please email me at andrewg@humaninvesting.com. If want to talk to an advisor, please email us at hi@humaninvesting.com.